Not at all a membranophone but rather part idiophone, part percussion

aerophone, The udu drum has been around for centuries, tempting subtle

rhythms from the master drummers of Nigeria and modern day

percussionists alike. Udu quite simply means ‘pot in the language of the

Ibo tribe of Nigeria, and a pot it literally is. Pots and percussion

seem to go together rather well. Pop down to the garden centre and see

for yourself. Tap a few and you will soon hear how some of them

resonate. You’II probably get a few odd looks, maybe even get thrown out

but what the hell, if it’s all part of the educational experience of

life then it must be of benefit.

Turn on to classical carnatic music from

South India and you’ll hear a pot called the ghatam. Listen to pot

players such as T H Vinayakram with Shakti and you’ll be blown away. In

a more Current Vein ,artists as Varied as Miles Davis, Sting and Jan

Garbarek have all used udus on some of their world tours and recordings.

If pots have been used so effectively as drums for so long, and across

so many continents, then there must be something in them, other than

air. Although both the Indian and the Nigerian pots are made of clay,

the udu differs From the Indian ghatam in one very important feature~

the number of holes. The ghatam has only one opening on its top, like a

normal water pot. The drum stands about 14” high, has no neck, and is

round in shape apart from the flat playing surface which leads up to the

hole on top. This opening is about 5” in diameter. Traditional players

spend most of the time playing the outside of the pot with their

fingers, wrists and thumbs, and use the airy ‘whoof whoof’ sound -

created by displacing air in the pot by hitting over the hole -very

sparingly.

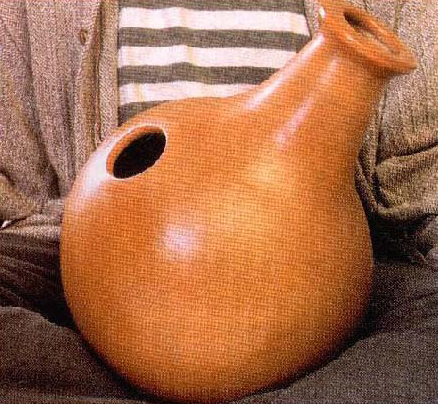

The udu on the other hand, is more of a side hole pot drum and has two

holes about 3” in diameter — one on the top and one on the side. Having

said this, I have seen pictures of ancient Nigerian pot drums which have

looked radically different, some having very wide holes on top and tiny

holes in the body of the drum. Traditionally it is more spherical in

shape than the ghatam, and has a narrow neck which leads up to the hole

on its top. The udu also comes in different sizes and traditionally

would make up a family of four drums in the same way as many other sets

of African drums. These four pots range in size from 18cm to 40cm in

height. Each drum would have a different pitch, the largest being the

bass voice and the smallest the treble voice. Some believe the deep

haunting sound lured from the sound chamber by the bare hand, to be the

voices of the ancestors, causing it to have significant involvement in

religious ceremonies

.

The origins of the drum have been traced back to Central and Southern

Nigeria, and it has been Found that, although we’re using the term udu,

the side hole pot drum is known by many different names, depending on

the tribal areas and particular ceremonies in which it is used.The

traditional method for making an udu is to pound a lump of soft earthen

clay over a firm spherical form known as a lump mould. The lump of clay

is placed on the mould and tempted into shape around it with a large

flat stone. It is then carefully beaten to uniform thickness with

handmade paddles a little like huge wooden spoons or ping pong bats.

Following this it is cut down to a half sphere on the mould. This half

sphere becomes the bottom half of the drum. The top half is then

constructed using the coil method, which involves building up long

lengths of clay, one upon another, before squeezing, paddling, and

shaping them up and into the sides of the drum. The important thing

during this process is to make sure that the sides are of uniform

thickness — this is of vital importance to the quality of sound of the

finished instrument. Building up the sides in this manner can be as slow

as one and a half inches per day, and can take as long as fourteen days

to complete.

After this, the side hole is cut and the drum is hand-rubbed with a

smooth stone to seal the surface. This has the effect of giving the drum

a deep lustre without using any type of glaze which might make it less

resonant. The drum is then dried under strictly controlled conditions

before it undergoes two firings — the first at a specific temperature

for hardness and sound quality, and the second in an outdoor kiln. It is

removed from this kiln whilst glowing hot and plunged into a container

of combustible material. Once removed from the ashes it reveals its

traditional black lustre finish. The whole process is said to take at

least one month. The work done during the early paddling

construction work has one very interesting consequence to note, that is,

the reformation of the tiny platelets which make up the clay. The

continuous pounding compresses, aligns and interlocks the platelets into

a strong, dense body which has similar properties to a hand-hammered

cymbal. The end result is a strong, resonant pot with two holes. We

could call it a single hollow sphere with a straight neck of calculated

length and width relative to the volume of the chamber (Fig. 1).

Helmholtz resonator is the general term used for resonators such as this

with non-tubular air chambers communicating with the outside air through

a single aperture (presupposing there is only one hole) Since the early

‘80s the existence of the udu drum has been developed, transformed and

made altogether more accessible thanks to the efforts of one man, Frank

Giorgini. With a Bachelor of Industrial Design, a Bachelor in fine Arts

in Education, and a Master of Fine Arts in Ceramics, along with his full

time ceramic sculpture studio and gallery in Freehold, NY, Giorgini

developed and once was solely responsible for supplying the whole

percussion world with udu drums. (Now companies like LP have taken the

torch where there once was risk).

Where is the divide between art and the

instrument? Why shouldn’t one make an instrument into a work of art at

the same time? Giorgini must he the only drum maker in the world to get

two of his instruments taken on by one of the major art galleries in the

world as permanent exhibits. Pop into the Metropolitan Museum of Art on

Fifth Avenue, NY and see for yourselves. If you can’t get there then you

can always try the Nassau County Museum of Fine Arts in Roslyn or the

Art Awareness Gallery in Lexicon, NY. It certainly brings another

dimension to drum making.

Since his involvement in 1985 with master Nigerian potter Ahbas Ahuwan,

Giorgini has spent his time developing the udu drum. This has manifested

in a number of ways. Besides making them stronger and more durable

(apparently not one has broken under a player’s hand), he has introduced

a whole new range of Udu designs. Some seem to look like bowling balls

whilst others look like molten dumb bells. Others look quite simply like

something you’ve never seen before. The drum can be played in a number

of ways; for example, by sitting cross legged on the floor, one can put

the drum in one’s lap with one hand over each hole. The hand on the top

controls the pitch while the other plays over the hole on the side. One

can use the palms, finger tips, slap in the fashion of conga playing, or

even play them with mallets or brushes. It is also possible tostand-mount

Udu drums and play them standing up.

Some of the contraptions for this purpose are quite extraordinary in

their own right and could probably find their way into an art gallery on

merit of their obscurity. Anyway, most percussionists could immediately

get a result on an udu drum, but particularly players who are used to

intricate passages with their fingers, i.e. - tabla players or Middle

Eastern percussionists. Udu drums have even been compared to tabla in as

much as some of the glissandos that can be produced are very similar to

the speaking voice of the bass tabla. Having spent years developing his

drumming pots Frank Giorgini decided he wanted to increase his knowledge

and went for some further field studies in Nigeria. “It was a bit like a

scene from a National Geographic article,” said Mrs Giorgini about their

journey from the States to Nigeria with a 15Ib udu pot in tow, to arrive

and have an audience with an important person in a mud hut. “It really

was a great honour for everyone.” Evidently the transfer of information

went both ways; the master Nigerian potter was so fascinated by the

shine on Frank’s drum that he got him to repeat his method several times

over until he had memorised it.

Further developments are leading to even

more elaborate looking drums. For example, it might he interesting to

look at the transformation the kim kim clay drum underwent at the hands

of Giorgini. These clay drums, along with a number of other side hole

drums, shekere, a woodblock, and a large clay drum played with a leather

paddle, provided the orchestral accompaniment to the women’s wing choir

of the evangelical churches of West Africa. This drum was basically a

double chambered pot which looked rather like a dumb bell. The drum had

a hole in each chamber and was played vertically with one hand hitting

the top hole whilst the other held the middle and changed the pitch by

moving the bottom hole on and off the thigh. Giorgini experimented,

making it larger and larger until it became too large to be played in

the traditional manner and had to he played horizontally with a hand on

each end like a double ended Indian drum. He also changed the shape of

the chambers to make the bass and treble more distinct from one another,

and curved the tubular middle section so the drum had both its playing

surfaces upright. The result, as you can imagine, is far from the norm.

If you are thinking of checking out an udu drum for your percussion set

up, now is a great time. There are plenty available at a very reasonable

price and they are ideal to experiment on.

|