This series of six articles was originally published

by Pete in the late 90's and looks at programming natural sounding drum

parts with human feel. Thanks go to Alex Van Laningham for

offering to type these articles out from the pdf scanned versions found

elsewhere on the site.

IN THE

GROOVE PART 1

Getting natural-sounding drum tracks is easy using

sampled loops, but what it you want to (or have to) program them up

yourself? In this new series Pete gives some programming secrets to get

your drum tracks into the groove...

For those of you out there with samplers, the goal of

getting a reasonably natural-sounding drum track sequenced up is not a

great leap of the imagination. However I know there are a lot of people

who spend hours stooped over the computer, embedded in the drum edit

page or step write mode writing grooves which never sound like anything

other then sequenced drum parts. Why? And how can this be changed?

Hopefully, these articles will give you an insight into how you can make

your sequenced drum parts more natural sounding and dynamic. The series

will centre around the event list and will look in detail at alt the

parameters, such as velocity, note length and exact timing at beats,

down to the smallest ticks.

THE EVENT LIST

To begin with, for those at you that have not

concentrated on the relevance of the even list, let’s take a look at

what it's all about. To begin with it looks complicated, but don’t

despair — its actually quite straight forward. All it tells you is what

you played. When you played it, how hard you hit, and how long the note

lasted. It also tells you what MIDI channel it was recorded on, and what

'Status' the event was (whether it was an odd a volume control message

or any other MIDI event). For the sake of this series, these last two

will always be set to note, and MIDI channel 10 - the channel most often

used for drums.

Right then, here is the event list. To begin with, we'll

look at the first four settings.

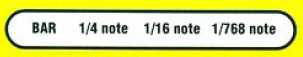

!Bar tells us in which bar the note was played. 1/4 tells

us in which 1/4 note of the bar the note was played. 1/16 tells us which

16th note with in the quarter note, and finally 1/768 pinpoints the

event down to the particular 16th divided into 48 pulses - 768 per bar

(it is possible to increase this on some programs to 1536 per bar.

Different programs display the event list differently but the general

approach is the same.) This time division of the beat may seem

unnecessary but, it is actually one of the most important tools in

making grooves sound natural.

We then have Status and Channel (as mentioned earlier).

Following this we have what are called the first data byte and the

second data byte, so called just to make something simple appear

complicated. This is what it actually means: First data byte is the note

you played, for example C#1 (C3=middle c). This identifies the note on

the keyboard you will need to hit to locate a particular sound. For

example, C2 is often a bass drum sound. Of course, if you have set up

your drum map, then each event for our drum grooves will be defined as

Hi-Hat, Bass Drum and so on. Second data byte shows the velocity of the

note you played. The only other thing to mention in the event list is

the note length. This is self explanatory and not so vitally important

with sequenced drums because of the short length of the drum sounds.

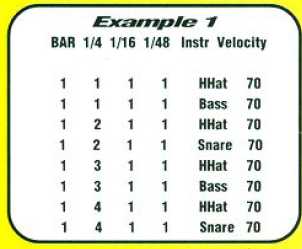

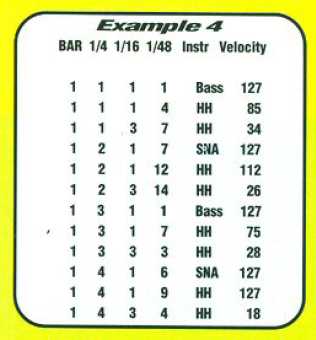

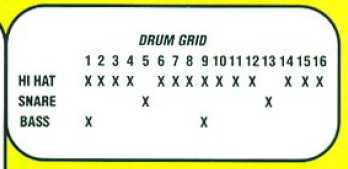

Right then, let's get onto the drumming. To begin with,

we're going to look at a couple of basic drum patterns which have been

the corner stone of drumming over the last forty years, and the patterns

a drummer learns first. Example one is about as simple as you can get.

Quarter notes on the Hi Hat, beats one and three on the bass, and beats

two and four on the snare. Write it in on the drum edit page with the

quantize set at 1/4 and this will be the readout for the first bar for

placement and velocity.

As you can see and hear, it's specifically on the beat

and rather dreadful. Notice how each beat is accurate, right down to

those semi-quavers divided in 48 bits. Even the velocities are

identical. Of course, you could humanize the rhythm with some of the

function in your program but, in my experience I've never found this

satisfactory in creating a natural feel.

Now let's look at the settings for the same rhythm as

played by, God forbid, a drummer on a MIDI drum kit. I've used the Power

Drum set on the Roland JV-1080 to write these rhythms. Played back on

some other kits in the same unit the general mix sounded different; for

example, played on the GM drum set, the Hi Hats got a little bit lost.

Bear this in mind, and choose a kit which represents all the sounds

clearly.

I find the readout of this rhythm quite extraordinary.

I've also kept in the first beat of the second bar. This happens to have

fallen in a very interesting place, as will be discussed in due course.

As you can see, although we started smack on beat one, by

the end of the first bar, we're thirteen pulses early. The first Bass

and Hi Hat or bar two have been included in bar one's list. I was

shocked when I first saw a readout of my playing in an event list. I

even tried to change it so as it was specifically accurate but, the

closer I got, the less natural it sounded. So then, as is evident, we're

anticipating the beat. If you look closely at the rhythm, other things

become evident. The Bass and Hi Hat, which should be together on the

beat three of the bar, have fallen apart by four ticks, as have the Hi

Hat and Snare on beat four, by two ticks.

As I mentioned, by the end of the bar, we're thirteen

pulses early. This can cause some problems when cutting and pasting

individual bars, but we'll discuss this in a later article. You would

think that if this carried onto its logical conclusion, then by the end

of the song the drums might be a bar or so ahead of the rest of the

tune, like two badly synchronised timecodes. This is not the case at

all. If we look at the remaining three bars of the example, we see that

it settles within the general parameters of being between two and

fourteen pulses ahead of the beat.

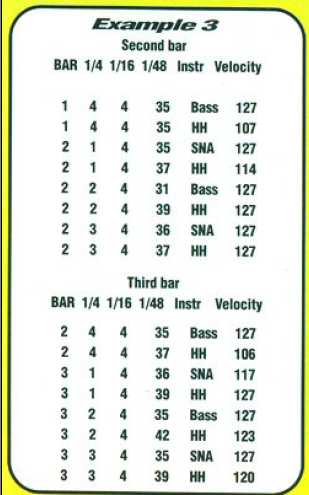

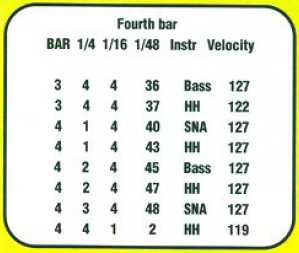

Here is the readout for the remaining three bars of the

rhythm. Don't forget, the first Bass and Hi Hat have been included in

the readout of the previous bar. As you can see from the lists below,

I've split them into their proper groups. This is how the first two

events of each list contain the previous bar number.

!

High velocity Next we're going to look at the velocity

readout for the first bar of our rhythm (See example 1). As Opposed to

all the velocities being identical. what we have is a range of different

velocities. This all becomes more striking in more complicated examples.

Bass drum and snare notes are consistent at a velocity of 127, though

they may well actually be above this. Its the Hi-Hats that prove to have

the most inconsistent velocity values in his example. Even so, they

remain quite high, never going below 99.

This first rhythm is only a simple one and doesn't

contain too many profundities. What I hope to have shown by looking at

it in this way, is how inaccurate The real thing actually is. If we take

away this inaccuracy, then we're taking away the main components of the

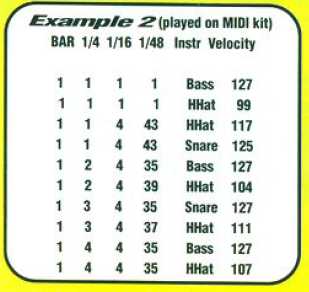

feel. This all becomes more interesting when we look at our second

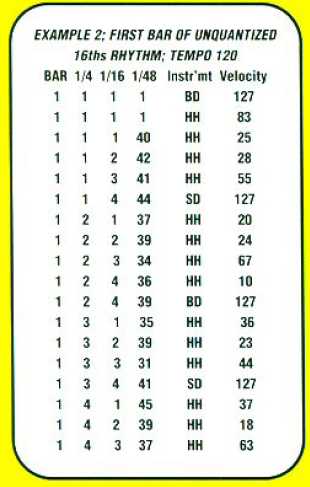

rhythm, basic eight-note rock. Obviously all the notes in the quantized

version will tall on the beat exactly so, let's go onto the version as

played in by our ever reliable real person. Look at the event list tot

the first bar (Example 2)

The first two things I notice about this is, unlike our

first rhythm, the notes are generally tailing behind the beat, and all

of the notes that should be together are actually a few ticks apart The

Hi-Hat is late on every beat, even on the first beat. Also of note are

the velocities of the Hi-Hat ranging from 18 to a maximum 127. It is

important to note That the Hi Hats falling on the beat are stronger than

those on the 'and' of each beat. The Bass and Snare are being Thumped

out at maximum volume and both seem consistent in their placement(of

course, if you wanted the velocities to be less than this you could

change them for the whole rhythm, then you could do this in the

Transform window or in an edit page. Remember, there are always lots at

different ways to do the same thing on all these programs. To keep the

balance of the rhythm the same, make sure you do an equal subtraction of

velocities for all the sounds).

Both Bass drums are accurate down to the finest tick.

This is amazing, because there was absolutely no quantize used at all.

The Snare, on the other hand, is falling 7 ticks late on beat two and 6

ticks late on beat four. Of course, one very important thing not to be

overlooked when looking at readouts like this is the tempo that they

were performed at. Quite un-imaginatively, these grooves were written at

120 bpm. This means 120 1/4 notes at 192 pulses per quarter note. This

is equivalent to 30 X 768 pulses (23,040) pulses per minute. Obviously,

if the tempo was different then there would be more or less pulses per

minute err, more or less. Let’s look at the second bar of the event

list.

Things change a little here. The Snare becomes

anticipated on beat two, whilst the Hi Hat ends up smack on the beat.

The same happens on beat three with the Bass and Hi Hat. Notice how the

Hi Hat and Bass Drum on beat one are three ticks apart, and also that

they are late. It is the combination of these factors which contribute

to what does and doesn't sound natural and grooving.

Velocities follow a similar pattern and shape. It is

important to balance all the sound in a logical way. For example, if the

Hi Hat is the same velocity as the bass and snare, then you'll end up

with a pretty un-dynamic sounding drum groove. The musical idiom you are

working in will dictate how you balance the drum sounds you program. If

you are working in a less ‘back beat' environment, then the velocity

levels of all the sounds might be closer to each other than if you

needed the bass and snare thumping out time.

One stylistic point which comes to light when we compare

our two rhythms is the role of the Hi Hat. It is clearly different in

both examples. In the 1/4 note example, its velocities are way up in the

comparison to the 1/8 note example. This is because the 1/4 note pulse

is being laid down so heavy in the first rhythm. Even thought the 1/4

note pulse is state in rhythm two, the velocities of the Hi Hats get

nowhere near as high.

Now we can move on to a lot more rhythmic examples and

basic philosophies of how and why drummers do what they do, and sound

like they sound. We are also going to look at some interesting

combinations of Drums and Percussion.

IN THE

GROOVE PART 2

Lets continue looking at programming drums and percussion

with an emphasis on getting as natural a feel as possible. To do this,

we are focusing on the event list and looking at rhythms through a

magnifying glass, stripping each beat down to its smallest sub division

of time, as well as looking at the dynamics, velocities and general

concepts behind the rhythm. Before we get on to building concepts and

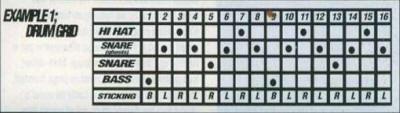

methods of ‘naturalizing' grooves, let's look at another simple rhythm

and re-familiarize ourselves with how we analyzed it last month. The

rhythm in question is a basic sixteenths beat for hi-hat, bass and

snare. Here is the readout as would appear in the event list. If we look

at example one, we see the stiffly quantized version with all the notes

falling exactly on the beat and all the velocities identical at 70. This

sounds particularly unmusical and unnatural. This is the art a good

drummer strives to perfect, adding groove to the music and driving the

song. Let's look the identical groove as played in by our trusty,

un-quantized drummer.

!

The first thing that is clearly evident is how the bass

and snare velocities stand out from those on the hi hat. It is quite

often the bass and snare which dictate the shape of the groove. Rhythms

on drum kit can be looked at as melodies constructed from phrases played

between the bass and snare. If sounds which are not an integral part of

this melody come in too loudly and confuse the clarity, then you may

well end up with a less effective rhythm than desired.

The same goes for percussion parts (we will be covering

percussion more later). Sounds such as open tones and slaps will dictate

the rhythmic melody. Other sounds such as muted tones should be very

much in the background and not interfering with the general shape. There

will be essential sounds in the foreground whilst the supporting tone

fabric will be in the background.

The next thing of note about our rhythm is it's pushed

nature, dictated by notes falling ahead of the beat by anything up to 15

ticks (Excluding the first hi hat and bass, pushed on to the first beat

by the program).

!

It is this anticipation of the beat which gives edge to a

drum pattern and helps it drive the song. (As apposed to ‘playing

behind the beat’ as one might do with a ballad.

Of course, it's not as simple as moving a whole quantized

beat ahead by a few ticks. If you look at the placement of all the Hi

Hats in our un-quantized pattern, you will see that it appears quite

random and on the edge of being wrong. As with last month's examples,

some notes are coming so early as to technically appear in the previous

beat. For example, the first snare beat comes a few ticks early on ‘ 1 1

4 44' as opposed to ‘1 2 1 1” in our quantized version.

If you look at the velocities of the Hi Hats for each

quarter note of the first two bars, you will see that there are no two

groups of sixteenths the same. This is one of the elements which keeps

the rhythm flowing. The fundamentals remain yet the time is quite

elastic. This gives us freedom to explore and experiment with rhythm

ourselves via the event list, without worrying about having to work with

hard and inflexible rules. Let's try an experiment.

Take the quantized version of the rhythm, loop the first

two quarter notes and go into the event list. First of all, bring the

bass and snare beats up by increasing the velocity to between 100 and

127. Now lets look at the hi hats and begin to alter their velocities.

Work slowly, adjusting one note's velocity at a time and seeing how it

affects the sound of the rhythm. The transformation will be very

gradual.

The velocity range of the hi hats should aim to be

between a quarter and half the velocity of the bass and snare. Don't

forget, you don't want all the Hi Hats to be identical velocities. Try

to find the dynamic shapes which sound most effective. For example, you

might want the hi hats to get louder during each 1/4 note, building up

to each man beat on the bass and snare.

Now the time has come to explore different timing

placements (it might be advisable to make backup copies before you start

to work on rhythms or else you might lose what you had in the first

place. It is often quite a good idea to work in an editor from which you

can escape if you do not like the changes you've made). More subtle work

and patience is required here. Get a general concept before you start

pulling the beat about. Do you want it to be ahead of the beat or behind

it? If so, by how much? How intense and driving do you want the groove

to be?

The image I have in mind when manipulating the timing of

a rhythm is the stretching of a piece of cloth. All the parts move in

relation to one another. If a part of the cloth is pulled tighter then

the parts nearer to it will move more than the parts farther away. This

is the concept that will keep your rhythms intact and not sounding

disjointed. Big angular leaps in the timing will simply sound wrong.

Experiment to find things which sound right for you. Work

with smaller adjustments before going on to more adventurous

alterations. To begin with the first few steps may sound odd,

particularly when you've only altered a few of the notes, leaving some

still quantized. Don't let this bother you as it all pulls into shape

the more you proceed.

When you're satisfied with your first altered groove,

save it as ‘Rhythmic template 1'. Then work on another and another,

giving yourself a number of building blocks which you can juxtapose in

any order to crate the desired flowing feel. Some work may need to be

done on seamlessly joining these parts together but more about that

later.

One thing to note is that if you end up using these

un-quantized grooves in work that has quantized patterns then it may

well sound out of place. You will need to make a template from the

un-quantized rhythm and use that to quantize the whole song, or at least

the parts that don't sit so well. It may sound like a lot of work but it

really is worth it in the end.

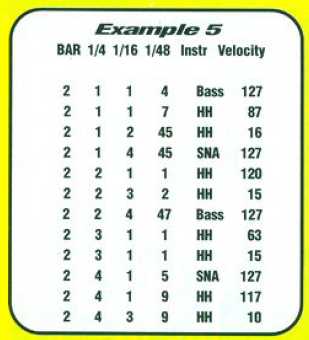

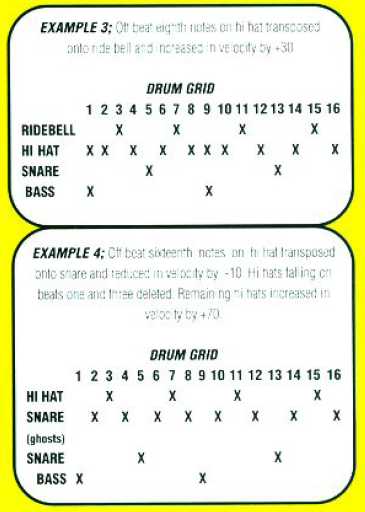

To finish off I'm going to look at a couple of different

voicings for our basic pattern. These involve taking our un-quantized

groove and moving some of the notes onto other drums in the same way a

drummer might do. In example three, I've changed all the Hi Hats falling

on the third sixteenth note of each beat onto the bell of the ride

cymbal. A simple voice substitution like this is exactly what might be

done to differentiate between the verse and chorus of a song.

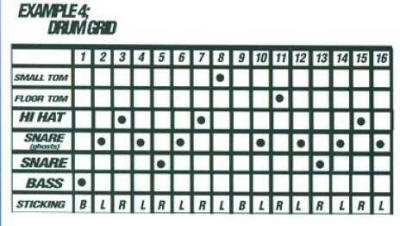

Example four is a further extension of this idea and

entails putting every off beat Hi Hat onto the snare drum. This is what

a drummer might do by moving his left hand from the Hi Hat onto the

snare. These notes would then be played as subtle ‘ghost' notes. Example

four also involves the exclusion of the Hi Hat played with the bass

drum. This creates a more off beat sound for the Hi Hat part.

Re-orchestrating these rhythms brings an interesting

point to light. Although all the velocities were fine for our original

pattern, they needed to be changed slightly to make the rhythms work

with different voicings. In example three the ride bell notes all had to

have their velocity increased by +30. This was because the offbeat bell

pattern became more a part of the overall rhythmic structure and without

it cutting through enough, the rhythm appeared to have gaps in it.

With example four the opposite had to be done for the

offbeat snare ghosts because the snare was dominating the rhythm and

obscuring the groove. All these off beat snares were reduced by –10,

leaving the main back beats on the snare at their uncompromising volume.

The remaining hi hats however had to be raised by a staggering +70 to

make the rhythm sound well balanced. The important thing in these

velocity alterations is that each transposed group had all its notes

altered by an identical amount. This helped to keep the natural shape of

the velocity levels as in our original.

IN THE

GROOVE PART 3

We'll continue from where we left oft last lime by

looking at different voicings for rhythms, and the 'drummer’s logic'

behind them. Here is the last example from the last article.

The event list readout is significantly different from

last month because I've played it in afresh, paying special attention to

keeping the snare ghosts as subtle as possible. This rhythm would

normally be played with the right hand crossing over the top of the

left, playing the hi hats and snare backbeats, whilst the left plays the

quieter snare ghosts. This positioning makes it easy for the right to

move around the kit playing different sound sources. This right hand

wandering technique is very common for drummers and makes some seemingly

complex patterns quite easy to play. For the moment I am deliberately

using simple patters with aim of getting the concept across. At eh end

of the day you will be much better off with the concept than a disk load

of grooves.

Here is example one including an indication of the

sticking used. As with all the examples in this article the tempo is

120. (Click the remaining images to enlarge).

Below left is the list of events from example one. Notice

how quiet the snare ghosts are. One might think that it would be

pointless to have notes with velocities as quiet as these but, if they

had not been played as part of the rhythm it simply would not sound the

same. It all contributes to the feel and groove of the rhythm.

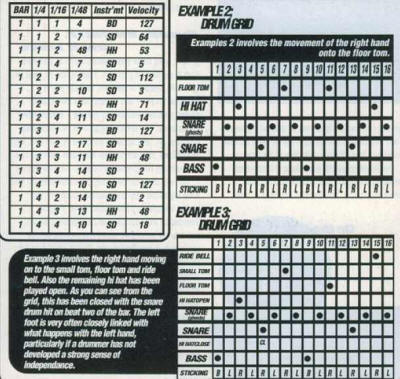

Example 3 involves the right hand moving on to the small

tom, floor tom and ride bell. Also the remaining hi hat has been played

open. As you can see from the grid, this has been closed with the snare

drum hit on the beat two of the bar. The left foot is very often closely

linked with what happens with the left hand, particularly if a drummer

has not developed a strong sense of independence.

Working from the bottom up, the next step might be to

start moving the left hand around the kit. The easiest way for a drummer

to do this would be to move up to the small tom. Example four

incorporates this technique. Notice how with all these rhythms the

sticking is unchanged. This demonstrates the many possible ways a simple

idea can be used. Of course, a drummer might not keep a rhythm as pure

as this, but all his deviations from the model would be with regard to

technical considerations such as these. The only thing I've had to

change to make this rhythm groove is the omission of the bass drum on

beat three of the bar. Try putting it in yourself and see how it pulls

the rhythm back and make it less exciting.

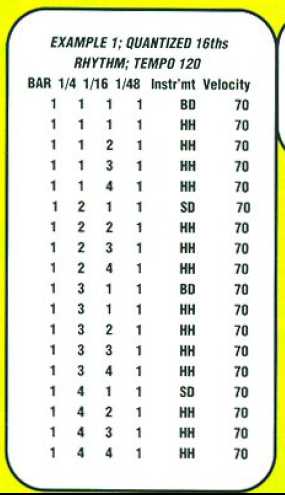

Example five is another simple manipulation of our

rhythm. This time I've made the phrase two bars long and removed the

first bass drum in the second bar. This is where the significance of the

ghost notes really stand out. Listen to how the rhythm falls away and

swells back in where the bars join. It is easy to fall into a trap of

adding things to improve the patterns as is evident from this rhythm, it

is often taking something away that is best. In this instance it

transpires that there is no bass drum in the second bar of the groove.

One thing some of you might have noticed about all the

rhythms this month is that they are all linear; that is, they are made

up of a string of single note, one after another. (Excluding the hi hat

closing in example three) This is a very common way for drummers to

compose rhythms nowadays. It adds a whole new dimension and serves as a

very adequate alternative to putting together independence-based rhythms

involving simultaneous sounds. It also helps create a lot of space and

clarity in a rhythmic structure. Example six is a typical example of

modern linear drum pattern. Here is the drum grid and event list for

this rhythm. It's interesting to see how full the rhythms sound bearing

in mind how few notes there are being used. Obviously, at different

tempos this would change considerably.

When the patterns begin to get more intricate and subtle,

so too will the velocity read out from the event list. This is clearly

evident from this example.

The first noticeable difference from our previous rhythms

is the velocities of the snare back beat and the bass drum notes. The

loudest bass comes in at 111 on the first beat of the bar whilst the

main snare accent on beat tour is a mere 82. This is because this rhythm

is back beat - orientated. The snare back beat for this particular

instance cuts through because of the subtlety of the ghost notes and

other parts of the rhythm.

Also of note is the velocities of the two bass drum notes

are played. The first is almost halt the velocity of the second, This

contributes strongly to the effectiveness of that little double push on

the bass drum. Try bringing up the velocity of the first to match that

of the second and see how it makes it feel less natural.

The shape at the rhythms timing is also worth mentioning.

Look at how it starts late, becomes slightly early by the two pushed

bass drums in the middle of the bar and gets gradually late again

towards the end, jumping in very small steps of timing as it does so.

The maximum it is ever out by is nine ticks and the biggest single leap

in time is five ticks. (One 16th note consisting of 48 ticks)

IN THE

GROOVE PART 4

So far we've been looking at some philosophies behind

drum patterns as played in real time and by a real drummer. This month

we're going to look at some basics of percussion technique and see how

percussion fabrics might be constructed.

We've all got sounds such as Conga Mute, Conga Slap and

Conga Open Tone on our sound modules – but how can we construct

natural-sounding rhythms using these sounds? Furthermore, how can we

combine other sounds such a Bongos and Claves to make authentic-sounding

rhythms? To begin answering these questions, we need to begin looking at

some of the basic techniques on the instruments. We're going to start

with Congas, and we'll use a set of two to begin with, to keep things

simple (in Cuba, Congas come in sets of anything between two and eight

drums).

As with the Drum Kit, the melodies of the rhythms are

constructed from main rhythmic lines – such as between the bass and

snare of Drum Kit – and supportive lines, such as played on the Hi Hat

or Ride on the kit. For the Congas, it's the slaps and open tones which

provide the main rhythmic fabric and the muted tones which stay in the

background. The basic building block of most Conga patterns is called

the ‘Tumbao' and is played on the low Conga (Tumbao actually means

‘repeating pattern'). It is on top of this that the high Conga would

play its patterns and both drums would make up the rhythmic melody. Here

are three different examples for both patterns. Notice how the patterns

lock in together and form what sounds like one drum pattern.

This really is the philosophy behind many Conga patterns

which in their cultural idiom would be played by different players. I'm

not a purist and am not trying to push any tradition only the concepts

behind that tradition. The concept here is to get a simple pattern on

the bass Conga and then come up with a pattern on the high Conga which

has open tones and slaps falling between the open tones of the low

Conga. Using this approach any patterns could be effectively used just

so long as they lock in well together. Here are our three interlocking

patterns. (Ex 1/2/3)

One thing to note about the high Conga patterns is the

absence of the muted tones in the rhythms. Normally when these patterns

are played between two drums, both of them would be filling in all the

unstressed parts of the beat with muted tones. Articulating this effect

on a general MIDI patch is more difficult unless you have a module which

lets you de-tune the individual drum notes to avoid the flanging effect

of having identical notes repeating at the same time. The only

successful way I found to do this was to de-tune one of the drums muted

tones.

I've avoided the problem in these examples by avoiding

the use of the muted tones in the high Conga part. Now let's look at

some of the velocities. Prominently low are the muted tones, leaving

space for the open tones and slaps to sing through. The mutes are very

understated indeed. It's quite clear to see that the slaps and open

tones on both drums are doing exactly what the bass and snare were doing

in our previous articles.

So far so good, but to begin building up the percussion

into a fuller fabric, there are three basic sounds one could add. Those

are metal, wood and shakers. These are what I think of a glue which bond

together in rhythm and syncopate it. The basic wood pattern would

generally be played on two wooden sticks called Claves. Here is the

basic pattern in three different forms.

The first is called the 3:2 Clave because there are three

beats in the first bar, and two in the second (these patterns are twice

the length of our previous Conga patterns)

The second is called 2:3 Clave because, er...!!!!

The third is a clave pattern with more of a flowing and

Brazilian flavour

For the metal pattern we might choose a Cowbell (or

something like Agogo Bells if we wanted a more Brazilian sound)

Like the Clave pattern the Cowbell pattern, has a 2:3 or

3:2 feel to it. This is not because it has three beats in the first bar

and two in the second, but because it locks in with the clave pattern

and because the main stresses of both patterns fall in the same place.

Therefore, if the 2:3 Clave is changed to the 3:2 Clave, then the

Cowbell pattern will also have to be changed. Here are both version of

the Cowbell pattern.

Finally come the Shakers, in this instance, the Marracas.

These bond the whole thing together by playing a steady eighth note

pattern.

We get the our full fabric by combining one from each of

the sections, ie one Conga pair, one Clave, one Cowbell and the Shakers.

This gives us quite a full-on traditional flavour, but if you use this

basic concept build a percussion fabric then you could create something

sounding anything but traditional.

IN THE

GROOVE

PART 5

The first things a drummer learns, besides how to play

the first basic beats are the rudiments. On the surface of things, these

can appear rather dry, boring, tedious, academic and destined to get you

more than half-way up the road towards the anorak shop. However, when

you delve a little deeper, then you can actually find a very usefully

tool in creating rhythmic fabrics.

For example let's take a very simple rudiment - the

paradiddle. This is quite simply no more than a sticking pattern

involving single and double strokes. The basis on the pattern is this.

The first way this might begin to be employed on the drum

kit is by placing each hand on a different sound source. To begin with

we'll play the rudiment with the right hand on the hi-hat and the left

hand on the snare. We will play this as sixteenth note rhythm. Then grid

for our rhythm will look like this.

As a step-written rhythm, this sounds pretty stiff and

uninteresting so let's get our MIDI drummer out of the box and see what

he comes up with. Here is the readout of the event list.

The first thing that is noticeable is that all the notes

falling on the beat are stressed, giving us our back beat emphasis. All

the other notes are played subtly and sit behind these strong points of

the rhythm and give it quite a flowing feel. Notice that the main

accents are falling on the second and fourth beats of the bar and the

snare velocities 109 and 128. Secondary accents are falling on the beats

one and three on the hi-hat (velocities 66 and 93). Most of the other

velocities are in the twenties apart from two hi-hats which rise a

little higher.

This velocity shape gives a seemingly boring linear

pattern some form, and makes it a much more interesting rhythm. The

timing of the pattern is also of interest. If you study the event list

closely, you can see that most of the strokes are falling late by

between five and twelve ticks. This adds a lot to the relaxed feel of

the rhythm. Remember in some of the previous articles the individual

strokes were often anticipated creating a rhythm which drove ahead much

more.

On inconsistency in timing within the rhythm is the

hi-hat which falls before the snare back beat on the fourth beat of the

bar this on hi-hat actually comes slightly early. It's thee odd little

inconsistencies which add to the natural fell of a real drummer

drumming. Logically speaking, one might never consider throwing in an

obvious inconsistency such as this into a programmed drum track, but I

would urge you to reconsider.

Anyway the rhythm actually sounds quite full at this

stage, even though there is nothing being played on the bass drum as

yet. It's a good thing to get a rhythm that works well without any bass

drum roles. This gives you the flexibility to copy this patter

throughout a whole section of a song, and then work on the bass drum

separately. This could have a number of advantages. For example you

might want the rhythm to flow smoothly yet also want to follow a very

off beat and varied bass line tightly. Simply copy the bass line to

another track, put it on the right MIDI channel for your bass drum sound

and bingo.

You might then go through the bass drum part and erase

some of the less important notes to allow the bass part some space. You

could also delay a few select bass drum notes to make it sound a little

more natural. Right then, lets loook at a few timing templates for the

bass drum so we can add these to our rhythm.

The next possible manipulation of the drummer’s rudiment

would be beat displacement. This simply means taking any pattern and

starting it one, two or however many beats later or earlier than the

correct placement.

For our rudiment in question, these next three examples

show how it would turn out with different placements. All these

examples can be mixed with the bass drum templates above.

The basic theory behind these rhythms is to come up with

a top line and then tailor the bass pattern to fit whatever piece of

music you might be writing. One style of drumming this immediately

brings to mind is the folk drumming of India. Whether it's played on a

pair of drums such as the Tabla or double-ended drums such as the Dholak

or the Dhol, the basic ideas behind the grooves are very similar.

A lot of Indian drumming entails drums which have the

treble sounds on the one end of the drum and bass sounds on the other.

It's very common to get continuous repetitive patters on the treble end,

whilst the bass end plays a more spacious and syncopated part (excluding

the wild rhythmic flurries very common in all Indian music)

To finish this article, I’m going to put a few patterns

of this style under the microscope, using help of our trusty MIDI

drummer. What we have are thee version of the 4/4 folk rhythm from North

India called Kherba. If you do not have access to any Tabla sounds in

your sound source then try a high bongo as the Hi Tabla sound, and a

deep floor tom or a subtle bass drum as the bass tabla sound.

The sounds I've used are the high pitched 'NA' sound

which is played on the rim of the small Tabla drum, the slightly lower

pitched TIN sound, which is played just inside the rim of the small

drum, and the low bass sound called. 'GE' (for those of you that might

not know, all the sounds on the tabla are represented by a phonetic

utterance. All the patterns that can be learnt on the Tabla can also be

recited in words).

I've reinforced the 'GE' sound in these examples with the

Udu pot open sound. This is not included in the grid or the event list

below. Just think of it as a sound employed to reinforce the bass drum.

The actual structure of these rhythms is very simple.

What makes them work in this context is the stressed and unstressed

beats. Take a look at the even lst for example five. We can immediately

see how the high pitched 'NA' sound is cutting through with it's

velocities. In many ways, it performs the roll of the drum kit in drum

kit rhythms. It is the sound most recognizable from the Tabla

repertoire.

IN THE

GROOVE PART 6

This sixth and last part of the ‘In the groove' series

deals with an area I've had quite a few enquiries about recently –

namely drum fills in the context of programmed grooves. Drum fills are

something you don't hear all that much about, and seem to be rather a

mystery to many non-drummers. To be honest, they are also frequently a

mystery to drummers, who think of this area of their art as an

opportunity for self-indulgence, rather than as a musical contribution

to lift a piece of music and help build bridges between sections.

Whatever way you look at it, drum fills are a totally

necessary adjunct to any drum pattern with the least aspiration of

sounding natural. One way to describe them is as rhythmic cadences which

pre-empt a change in musical passages. Drum fills are effective when

they maintain the feel and flow of the music without detracting from the

point at hand. If it stands out like a sore thumb by speeding up or

slowing down or because the drummer is being heavy-handed and unsubtle,

then it's not the drum fill for the moment.

So how do we go about programming effective – and musical

– fills?

There are a few basic principles behind the sort of fill

a real drummer might play. Although it may appear rather obvious, a

drummer has two arms and two legs and therefore can't continue playing

the rhythm while executing the fill. This is what makes programming

fills difficult – to keep the feel of the rhythm while the groove isn't

happening is a challenge indeed.

Next come tonal considerations. If the body of your

rhythm is tom tom based and you want a fill to stand out in contrast,

then it might work to employ the snare, or some accents and pushes on

cymbals and open hi hats. Similarly, if the groove has been more hi

hat/snare/bass drum rooted, and then an adventure around the toms might

be the thing to do.

Rhythmically, it might be wise to use the general

contours of your main rhythm as a template for the fill. Alternatively,

you could transpose elements of the rhythm onto other drum sounds. Go

into the list edit, tinker with a few velocities and bingo.

Anyway, I'm going to cover six fills and explain some of

the concepts involved. Each fill is one bar long and is preceded by one

bar's groove. Most of the six fills are linear-based, in as much as they

are constructed from single sounds (a linear drum pattern is a pattern

that does not use two different sounds at one time).

!

The building block of the first fill is contained in the

first four semiquavers. This 'drum lick' is very common amongst drummers

and can be heard on a lot of recordings in many different musical

idioms.

The basis of the pattern is four notes long, starting on

the high-pitched snare and going on to the small tom, floor tom, and

then the bass drum. Each note could be conceived of as slightly lower in

tone than the last, adding tonal shape to the concept (of course, you

could always do the opposite, starting on the lowest tone).

The other relevant factor for this is the sticking that

would be used by a drummer to articulate it on the drum kit. For a

right-handed player this would be played in this order:

Right-Left-Right-Bass. This is what leads on to the rest of the fill.

The sticking remains the same but is played on different drums. There

are also two double beats on the bass drum after the second and third

repeats of this pattern.

The second fill is a common drum fill found on a lot of

pop records. It is based on the common or garden ‘single stroke roll'

with the leading hand venturing onto the toms.

There is a lot of space in this fill, and it is very

important not to cram every available space with a drum beat. It might

be the only drum fill in an entire song, but that is no reason to

overcrowd it. It might seem perfectly logical that continually adding

things will necessarily make a composition fuller, but it is more often

the case that subtracting something adds more to the end result.

Notice in particular the subtle ghost notes in this fill.

It is the subtlety of these notes as they lead up to the accented parts

of the groove that really make this one work for me.

The third and fourth fills are also based on this single

stroke (R-L-R-L) pattern but involve the movement of both hands around

the toms. Try going into the list edit or the score edit and transposing

the various elements onto different drums, and see what you come up

with.

Example five involves a three-beat pattern which is

played around the toms, descending from high to low and ending on the

snare with a ‘flam' (an accent which is preceded fractionally by a quiet

note – these are very effective in fills and can be used on toms or any

sound source you could choose to think of).

This fill is brought to its conclusion with a meaty crash

on a Chinese cymbal. These cymbals can also be very effective when

they're used as reinforcements to snare drum accents.

Notice how all these fills include the first beat of the

following bar. In each instance, these are falling early, just before

the end of the fill-in bar. This is because the fills are slightly ahead

of the beat and are pushing the tune – if there were one – into the next

section (for a detailed explanation of timings in the event list, you

ought to look at the previous five articles in this series). This means

that when you write the rhythm that follows on from the fill, you will

have to omit the first bass drum and hi hat in the first bar of the

pattern to avoid the flanging effect of having two bass drums sounding

at once.

You might also need to tinker a little in the event list

to make a neat join. I always prefer to omit the first bass drum of the

rhythm rather than the last bass drum of the fill, because it seems to

keep the integrity and feel of the fill intact.

The sixth fill is slightly longer and starts around

halfway through the last bar of time. This brings another important

hypothesis to light: namely ‘kick off notes' – otherwise identifiable as

starting places for your fill.

A fill really does not have to be one bar long. It can

start anywhere in the contours of your rhythm. This fill catches the

listener by surprise because it is slightly off beat and syncopated. The

real starting point for this fill is on the sixth eighth note of the

penultimate bar. A repeating three-beat pattern (Right-Left-Left) is

then explored with the right hand moving around the kit and comes to a

climax with a flurry of accents and ghost notes on the floor tom and

snare. This sort of syncopated effect can easily be obtained by thinking

of an equal bar as comprised of lots of different-length units. For

example, a bar of sixteenths could be divided 5+5+6(=16)

If you have worked on these

examples, please send me the midi files and audio so I can add that for

other users. You will be credited. Also, if this has helped

you get natural sounding grooves then send me the results and I will

post it on this page if it is good.